The Shroud of Turin and the Sudarium of Oviedo are two of the most famous and intriguing relics in Christian history, and they are believed by some to have a direct connection to Jesus Christ. The Shroud of Turin is located in the Cathedral of Saint John the Baptist in Turin, Italy.

The Shroud is a linen cloth that bears the image of a man who appears to have suffered physical trauma in a manner consistent with crucifixion. The shroud is one of the most studied and controversial artifacts in human history, with many believing it to be the burial shroud of Jesus Christ.

In his gospel, The Apostle John provides a detailed account of the burial cloths he observed in the tomb. He initially references ‘linen cloths,’ or as some translations of the gospel phrase it, ‘linen wrappings.’ The original Greek term used here is ‘ta othonia,’ which translates to ‘pieces of fine linen.’ This term, interestingly, is distinct from the ones used in the other gospels, yet conveys a similar meaning. Notably, the term is in the plural form, which contrasts with the other gospels that mention only a single cloth used to wrap the body of Jesus. This implies that John is referring to more than one piece of cloth.

John’s narrative also highlights another cloth, described as ‘the cloth that had been over his head.’ The Greek term for this is ‘to soudarion,’ derived from the Latin ‘sudarium.’ This term typically signifies a ‘face cloth’ or ‘towel,’ commonly used for wiping or drying the face. John notes that this particular cloth was positioned separately from the other linen cloths, either rolled up or folded in a different location.

John’s belief, as he describes, was cemented upon seeing these cloths. He infers that if the body had been stolen, it would be unlikely for thieves to take the time to carefully unwrap the body and meticulously place the cloths in their respective positions. This observation led him to believe in the resurrection. Early Christian writers have often pointed to this reasoning of John, emphasizing the significance of the orderly placement of the cloths as a factor in his realization and subsequent belief in the resurrection. This detail about the cloths thus holds a unique place in the Christian narrative of the resurrection.

Over the centuries, the Shroud passed through various European owners, eventually reaching the House of Savoy. In 1578, it was moved to Turin, Italy, where it has remained, except for brief periods during wars.

Blood Analysis: Studies have been conducted on stains believed to be blood, revealing details consistent with the wounds of crucifixion. Blood type AB has been reported in some studies, though these results are controversial.

Pollen Analysis: Pollen grains from various plants, some unique to the Middle East, were reportedly found on the shroud, leading some to suggest it was in that region at some point.

Carbon Dating: In 1988, radiocarbon dating tests were performed on samples of the shroud. The tests dated the shroud to the Middle Ages, between 1260 and 1390, suggesting it was not old enough to be the burial cloth of Jesus.

Critics of the carbon dating point to potential contamination that the tested sample was from a medieval repair patch rather than the original cloth. Researchers who dispute the 1988 carbon dating results suggest that the samples tested were taken from an outer corner section of the shroud that was repaired in the Middle Ages using a technique called “invisible reweaving.” This theory posits that new material was expertly woven into the original cloth, skewing the radiocarbon dating results.

Lack of Broken Bones: In crucifixion, a method often employed by Roman soldiers involved the breaking of the victim’s legs while they were still on the cross, a practice intended to hasten death. The legs of the man from the shroud are crossed, but not broken – as was the usual custom of Roman soldiers to do when dealing with crucified victims.

This specific act of not breaking the legs holds significant importance in Christian theology, as it aligns with a prophecy from Psalms 34:20: “He keeps all His bones: not one of them is broken.” This prophecy was seen as foretelling the fate of Jesus Christ, whose legs were not broken during his crucifixion. This detail is considered a fulfillment of the prophecy and is often linked to the belief in Jesus’ divine mission and identity. Jewish law prohibited a crucified person from hanging on the cross during Sabbath. To hurry the process, Roman soldiers could decide to break the leg bones of the victim. In contrast, the two individuals crucified alongside Jesus did have their legs broken, as was typical in Roman executions, further highlighting the unique circumstances of Jesus’ crucifixion.

Pierced Right Side: In John 19:31-34: When they got to Jesus, they saw that he was already dead, so they didn’t break his legs. One of the soldiers stabbed him in the side with his spear. Blood and water gushed out. Since the the soldiers did not break Jesus’s legs, the centurion Longinus pierced his side. On the Shroud, the significant injury on the right side of the chest is clearly visible, positioned between the fifth and sixth ribs. Blood is observed flowing downward, consistent with what would be expected from someone in a crucifixion posture.

The Shroud of Turin is a highly debated topic. It is certain that individuals with a strong faith can derive significant benefits from these observations and conclusions.

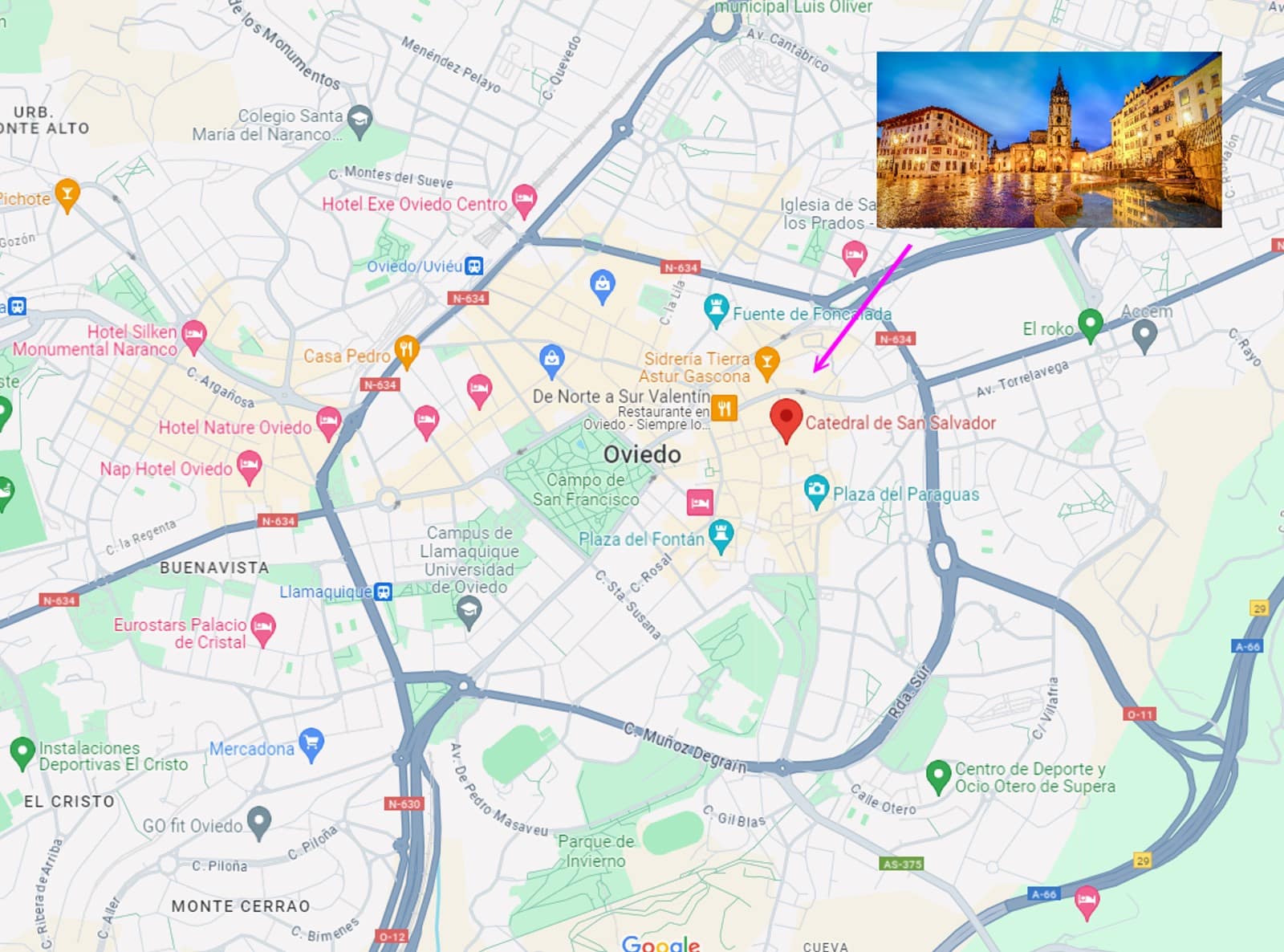

Sudarium of Oviedo

This is a bloodstained piece of cloth kept in the Cathedral of San Salvador, Oviedo, Spain. It is believed by some to be the cloth that covered the head of Jesus Christ after his death, as mentioned in the Gospel of John (20:6-7). Unlike the Shroud of Turin, the Sudarium does not bear a discernible image. Its main significance lies in the bloodstains and fluid marks that are consistent with those of a crucified individual.

The connection between these two relics is often made through their bloodstains. Studies have been conducted to compare the blood and serum stains on both cloths, with some researchers suggesting that the patterns and blood type are consistent between the two. This has led to the hypothesis that they could have covered the same person – Jesus Christ.

Early History: Its earliest documented history begins in the context of Jerusalem in the 1st century AD. However, concrete historical records are scarce.

Journey to Spain: The Sudarium of Oviedo cloth is believed to have been taken from Jerusalem to northern Africa and then to Spain. By the 7th century, it was reportedly in Toledo, Spain. When the Moors invaded Spain in 711, the cloth was taken to Oviedo in the north, to be kept safe from the invading forces. Since 842, it has been housed in the Cathedral of San Salvador in Oviedo, Spain. It is kept in a special chest, known as the Arca Santa, along with other religious relics.

Connection to the Shroud of Turin

Similar Bloodstains: The most significant connection between the Sudarium of Oviedo and the Shroud of Turin is the bloodstains. Studies have shown that the bloodstains on both cloths are of the same blood type (AB) and appear to match in terms of the placement of the stains, suggesting they could have covered the same head.

Forensic Analysis: Forensic studies have been conducted to compare the patterns of the bloodstains and the possible wounds that would have caused them. These studies suggest that both cloths might have been used on the same person. Stephen E. Jones makes a compelling analysis suggesting the two are from the same person.

Pollen Evidence: Pollen analysis has also been used to draw connections between the two. Pollen grains from the Middle East have been found on both cloths, supporting the theory that they both originated in that region.

Viewing The Sudarium of Oviedo

Address: Pl. Alfonso II el Casto, s/n, 33003 Oviedo, Asturias, Spain

Phone: +34 985 21 96 42

The Sudarium of Oviedo is located in the Cathedral of San Salvador in Oviedo, the capital city of the Asturias region in northern Spain (SV). The Cathedral was founded by King Fruela I of Asturias in 781 AD and is located in the Alfonso II square. The cathedral, also known as the Oviedo Cathedral, is a significant historical and religious site.

To see the Sudarium of Oviedo, you would typically need to follow these steps:

Plan a Visit to the Cathedral: The first step is to plan a visit to the Cathedral of San Salvador in Oviedo. It’s advisable to check for any specific visiting hours or requirements, especially if you’re traveling from afar.

Special Display Times: The Sudarium is not on permanent public display. It is usually shown to the public only three times a year: on Good Friday, on the Feast of the Triumph of the Cross (September 14), and on the Feast of the Holy Shroud (the Sunday following September 21). It’s important to plan your visit accordingly if you wish to see the Sudarium.

Viewing Arrangements: During these special display times, the Sudarium is usually exhibited in a case for visitors to view. The specifics of the viewing arrangement might vary, so it’s a good idea to check the latest details from the cathedral’s official sources or local tourist information.

Other Opportunities: For those interested in the Sudarium but unable to visit during the display times, the cathedral might offer other opportunities, such as exhibitions or guided tours, that provide more information about its history and significance.

Is There A Connection?

In an Aleteia article from 2016 it is stated that The Shroud of Turin and the Sudarium of Oviedo “almost certainly covered the cadaver of the same person.” This is the conclusion from an investigation that has compared the two relics using forensics and geometry.

The research was done by Dr. Juan Manuel Miñarro, a sculpture professor at the University of Seville, as part of a project sponsored by the Valencia-based Centro Español de Sindonología (CES) (The Spanish Center of Sindonology).

The study highlighted significant correlations between the two cloths, such as the number, distribution, and types of bloodstains, and morphological similarities in the markings and wounds. These correlations exceeded the typical criteria used in judicial systems for identifying individuals, providing more than 20 points of comparison.

Furthermore, the research found specific alignment in the bloodstains and wounds on both cloths, particularly in areas like the forehead, back of the nose, right cheekbone, and chin. While there were morphological differences in the bloodstains, these were attributed to different factors such as the duration and intensity of contact, and the elasticity of each cloth’s weave.

Given these findings, experts involved in the study stated that it is now challenging to believe that these cloths covered different individuals. The number of coincidences between the wounds and lesions on both cloths makes it seem improbable that they are from different people. The study, therefore, significantly strengthens the argument that both the Shroud of Turin and the Sudarium of Oviedo were used on the same person.

Likewise, The Spanish Center for Sindonology, based in Valencia, engages in scientific research related to the Sudarium. This institution received permission to conduct a multidisciplinary study of the cloth in 1989. Their investigation has demonstrated the overwhelming probability that the Shroud of Turin — which many believe to be the cloth in which Jesus’ crucified body was buried — and the Sudarium of Oviedo actually covered the same crucifixion victim.

First International Conference on the Shroud of Turin further summarizes the conclusions of the research conducted by the Spanish Center for Sindonology.

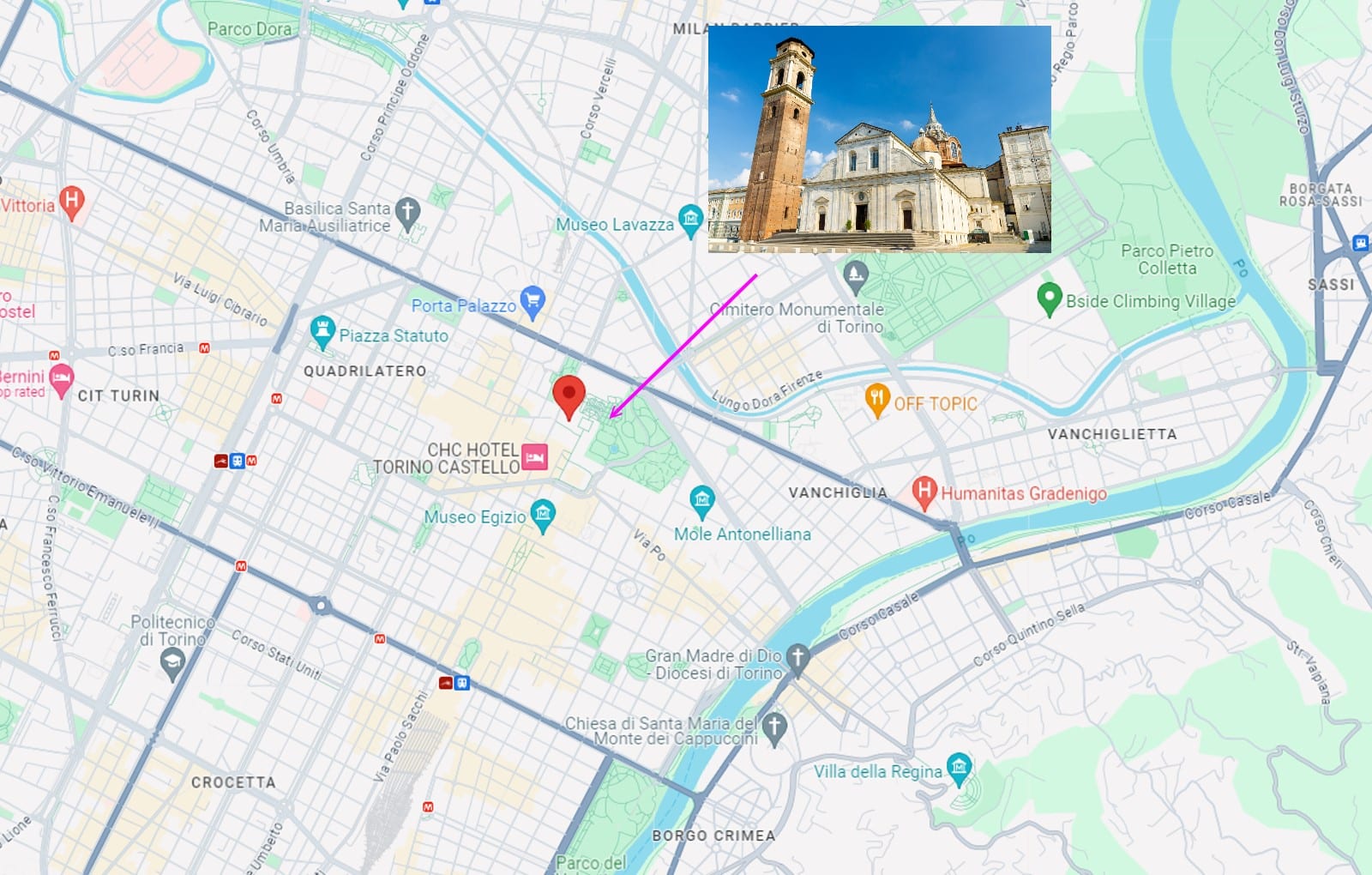

The Shroud’s Location

Address: Cathedral of Saint John the Baptist, Piazza San Giovanni, 10122 Torino TO, Italy

Phone: +39 011 436 1540

The Shroud of Turin is located in the Cathedral of Saint John the Baptist (SV) in Turin, Italy. However, viewing the Shroud is not as straightforward as visiting most historical artifacts or artworks, due to its special status and the care taken in its preservation.

Special Exhibitions: The Shroud is not on permanent public display. It is exhibited only on special occasions, often at the discretion of the Pope or the Turin Archbishop. These exhibitions are known as “public ostensions” and happen infrequently.

Planning for Ostensions: When a public ostension is announced, it is a significant event, attracting pilgrims and visitors from around the world. Information about dates and viewing procedures is typically provided by the Diocese of Turin and can be found on their official website or through announcements in Vatican communications.

Tickets and Reservations: Depending on the nature of the exhibition, visitors may need to secure tickets or make reservations. These exhibitions are often free, but due to the large number of people who wish to view the Shroud, a reservation system is usually put in place to manage the crowds.

Online Viewing: For those unable to visit Turin during these rare exhibitions, there have been occasions when the Shroud was made available for viewing online. For instance, during special events or periods of global significance, the Church has sometimes arranged for live broadcasts or online exhibitions.

Visiting the Cathedral: Even when the Shroud is not on display, the Cathedral of Saint John the Baptist is itself a significant historical and religious site. Visitors can explore the cathedral and often find information and exhibits related to the Shroud.

Next Exhibition: To find out when the next public exhibition of the Shroud will be, it’s best to keep an eye on announcements from the Vatican or the Diocese of Turin. These are typically made well in advance to allow for international visitors to plan their trips.

What is a Religious Traveler?

A religious traveler is not just a tourist, but a seeker of knowledge, spiritual enlightenment, and historical truths, driven by a desire to experience the diverse manifestations of faith and devotion around the world. They explore various temples, shrines, churches, mosques, and other holy places, seeking deeper understanding and connection with their faith. Their journey is as much about internal exploration and finding personal peace, as it is about understanding the tapestry of religious beliefs and practices that bind humanity.